There was just no keeping Mary Kingsley down

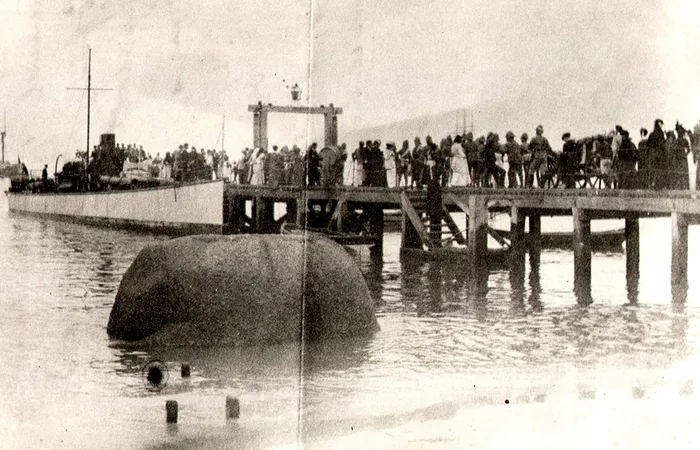

Mary Kingsley’ funeral cortège in Simon’s Town.

English explorer, scientific writer, ethnographer and nurse Mary Kingsley spent just two months in South Africa, in 1900, but in that time she helped to turn a “near mortuary” for Boer prisoners of war in Simon’s Town into a place of healing.

Cathy Salter, curator of the Simon’s Town Museum drew information from the Simon’s Town Historical Society Bulletin and Mary Kingsley, Imperial Adventuress, by Dea Birkett, to tell Mary's story.

Mary Kingsley was born in England on October 13, 1862, the eldest child of physician, traveller and writer George Kingsley and his wife, Mary Bailey. “As a girl of her time, she was not expected to achieve much in her lifetime other than a suitable marriage," says Ms Salter.

Mary had little formal education but she held a fascination for the outside world and spent many hours in her father’s well-stocked library.

At 30 years of age, having had to nurse both her parents through ill-health and ultimately their death, she remained unmarried.

After her parents’ deaths in 1893, Mary travelled to West Africa, alone.

She landed in Sierra Leone and travelled as far as Angola, living among the indigenous populations and learning about their cultures.

During a subsequent trip in Gabon in 1894, Mary, collected fish specimens previously unknown to Western science, three of which were later named after her: Brycinus kingsleyae, Brienomyrus kingsleyae and Ctenopoma kingsleyae.

Mary published two books about her travels: Travels in West Africa (1897), which was an immediate best-seller, and West African Studies (1899). Both works gained her respect and prestige within the scholarly community.

When the Anglo-Boer War broke out in 1899, Mary travelled to South Africa on a troopship and volunteered as a nurse.

Mary reported to surgeon-general Sir William Deane Wilson, the principal medical officer at the Castle, who asked her to tend to POWs in Simon’s Town. There, Mary found a humanitarian crisis, with large numbers of Boer POWs having contracted fatal “camp fever” (also known as enteric fever or typhoid). Measles and other diseases were rampant too.

Dr Gerard Carré had just arrived in Simon’s Town, as had two nursing sisters. Medical supplies were in very limited supply and narrow iron beds covered in hessian sacking stood in the four rooms, designated as wards.

Mary wrote to her friend in England: “I never struck such a rocky bit of the valley of the shadow of death in all my days as the Palace Hospital. There are the never-to-be-forgotten bugs and lice. The Palace supplies bugs free of charge.”

Two more doctors and three more nursing sisters arrived - as did more medical supplies - but the conditions remained dangerous.

Mary wrote at this time: “All this work here, the stench, the washing, the enemas, the bedpans, the blood, is my world.”

More than 100 men were placed under Mary’s sole care.

It was Dr Carré who later said that Mary had “turned a mortuary into a sanatorium”.

Typhoid raged through the hospital. Many died.

Ms Salter says that despite being a teetotaller, Mary believed that Cape wines would boost her physical well-being and morale, and that smoking would offer some protection against infection.

“Sadly, this was not the case and she too caught enteric fever,” says Ms Salter. “Dr Carré performed an operation to try to save her, but she died of heart failure and enteric fever on June 3, 1900, just over two months after her arrival in Simon’s Town.”

Aware that she was dying, Mary asked to be buried at sea.

Her body was moved to the main army barracks and the cortège proceeded to the Town Pier the following day. The large teak coffin was drawn on a gun carriage, escorted by the Fourth West Yorkshire Regiment, playing the Dead March, and a detachment of the Royal Artillery.

Crowds gathered, lining the street all along the route. A service was conducted on the Town Pier by Reverend J.P. Legg, rector of Simon’s Town and acting military chaplain.

The HMS Thrush, together with a firing party from the Royal Marine Light Infantry took her body out and committed her to the sea beyond Cape Point, in a solemn funeral ceremony.

This was swiftly followed by consternation on the part of the mourners, when it was discovered Mary's coffin had not been weighted sufficiently, and bobbed off into the ocean.

"Mary’s friends and family however believed that the incident would have been the source of much amusement to her, for though she had professed to believe in a higher power, Mary had questioned the role of Christian missionary endeavours in Africa, believing them to be of questionable benefit to indigenous Africans," Ms Salter says.

The lifeboats of HMS Thrush were launched and eventually the wayward casket was captured, secured to a spare anchor and committed to the deep.

On Saturday April 1, 1905, when the Simon’s Town Cottage Hospital was opened for the admission of civilian patients, one of its four wards was named the “Nurse Kingsley Ward”.

This hospital moved to Fish Hoek and is today known as False Bay Hospital.

Ms Salter says the ceremonial funeral and honours afforded the unmarried 37 year-old Mary were rare, and serve as testament to the impact she made during her 66-day mission in Simon’s Town.

The writer Rudyard Kipling and his family, who were living in Woodstock at the time of her arrival in Cape Town, called Mary the bravest woman he knew.